|

LayerProcGen v0.1.0

Layer-based infinite procedural generation

|

|

LayerProcGen v0.1.0

Layer-based infinite procedural generation

|

Deterministic contextual generation is possible by dividing your generation processes into multiple layers and keeping a strict separation between the input and output of each layer.

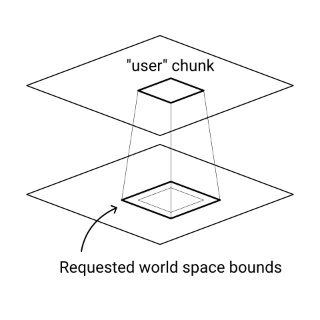

As part of its generation code, a chunk can request data from another layer:

In this context we can call the chunk a "user" chunk, since it's using data provided by another layer.

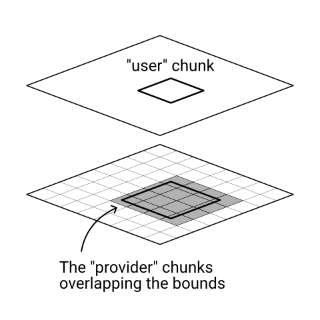

The other layer returns the requested data to the “user” chunk as follows:

Note that “user” and “provider” do not refer to different types of chunks, but specify relations. Chunks are commonly “users” and “providers” at the same time.

In order for a layer to return data within specified bounds, the “provider” chunks overlapping those bounds must first be generated.

The LayerProcGen framework uses an approach for this where “provider” chunks are generated before the “user” chunk even starts being generated. This means dependencies must be known ahead of time.

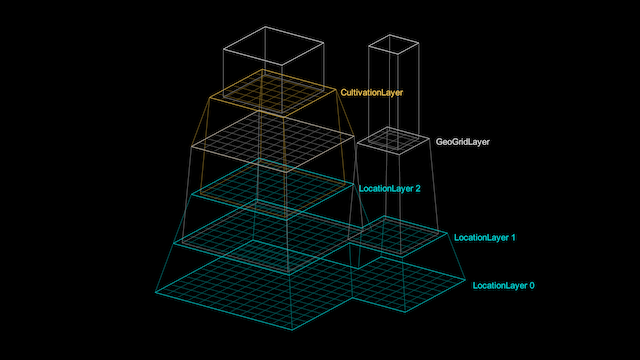

We can redefine dependencies between chunks as dependencies between layers:

There is potential for human error when specifying the padding for a layer dependency. If the data requests in the generation code use larger padding than the layer dependency specifies, the data request may be unsuccessful due to the needed chunks not having been generated. However, runtime errors will be logged, and they specify which padding is required to fix the issue.

Regular layer dependencies ensures that chunks are created when they are needed by other chunks. But to make any chunks be generated in the first place, we need to specify top layer dependencies, as all generation starts with one or more top level dependencies at the root.

A top layer dependency specifies that chunks from a specified layer are required within given bounds. Those bounds are specified as a focus point and a size, with the focus point indicating the center point of the bounds. Typically a top layer dependency is focused on the player's position in the world.

Multiple top layer dependencies can be specified, and they can depend on different layers. If any chunks in any layers end up being simultaneously needed, directly or indirectly, by more than one top layer dependency, they are only generated once. In other words, overlapping dependencies do not incur any extra cost.

Some typical use cases for top layer dependencies are:

It's worth noting that different gameplay features may not need the same things generated. Displaying a map can likely skip generation of a lot of data needed only for creating the world in greater detail.

Perhaps generation of the world itself is sufficiently slow that the player can only move with a certain speed through it in order for the generation to keep up. But the generation of the map may be light-weight enough that the player can scroll around the map screen quickly. It's a good idea to design data layers with such concerns in mind.

Generation of a world may not necessarily have a single top layer that a top layer dependency can naturally depend on to trigger generation of all aspects of the world. Maybe a PropsLayer generates static Prefabs like rocks and buildings, while an NPCLayer generates NPCs, and neither depend on the other. Possibly the PropsLayer need to generate props within a larger radius of the player than the NPCLayer needs to generate NPCs.

It's also possible that the PropsLayer depends on a TerrainLayer which generates terrain, but you want the terrain generated in a larger radius than what the PropsLayer needs.

There are two ways to go about this:

In mathematics and computer science, a graph is a set of objects with connections between some of them. In a directed acyclic graph (DAG), only one-way connections are allowed, and they may not form cycle (loop).

In the LayerProcGen framework, layer dependencies implicitly form a directed acyclic graph, with each layer dependency being a one-way connection between two layers. Internal layer levels also count as separate objects in the DAG.

The framework doesn't explicitly build or store this graph structure, but it's implicitly defined by the layer dependencies you specify in your layers.

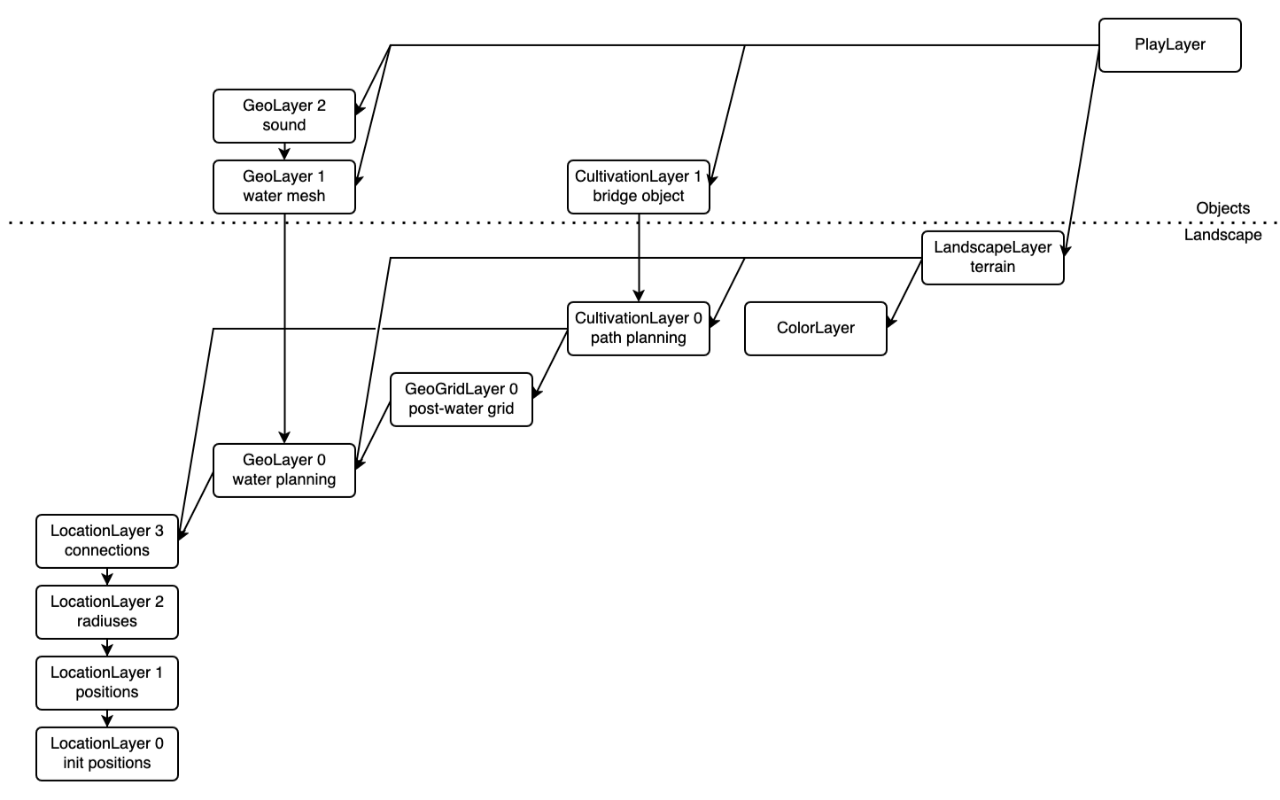

If you end up creating a lot of layers, it can be useful to map out the dependencies in a visual graph to better be able to keep an overview of which layers and levels depend on which. There is no one right way to design such a visual aid, but here is one example: